Exploring Trie Data Structures: A Brief Exploration

Go Trie Implementation

If you just want a Go Trie implementation to copy and paste, just jump to the end.

A Trie, also called a digital tree or prefix tree, is a type of tree data structure used for locating specific keys in a set. I will go under the assumption that you probably have some idea of how tree data structures work.

The biggest differentiators of a Trie from a binary tree or any of the more familiar trees are the number of child nodes and the key associated with each node.

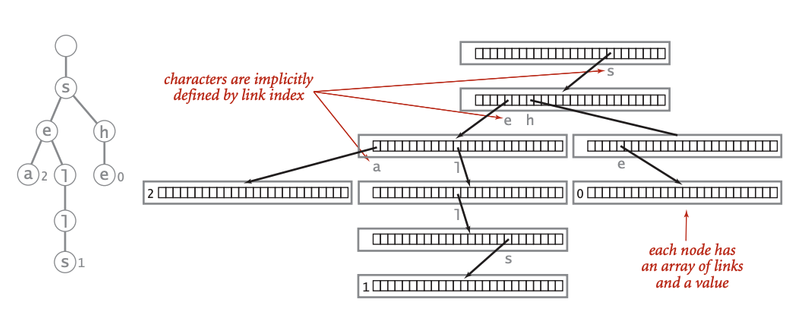

- A Trie node has m child nodes for each node. m being the size of the alphabet, so if our strings are exclusively lowercase English then our alphabet is 26 letters.

- A Trie node has no value; the value is defined by the node’s index in the parent node (this will make more sense soon).

We are now going to build our own Trie Tree to better understand the concept, starting with pseudo-code and ending with working Go code.

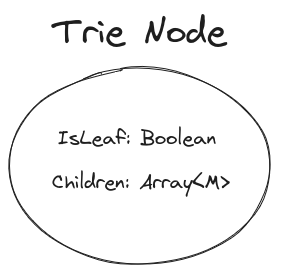

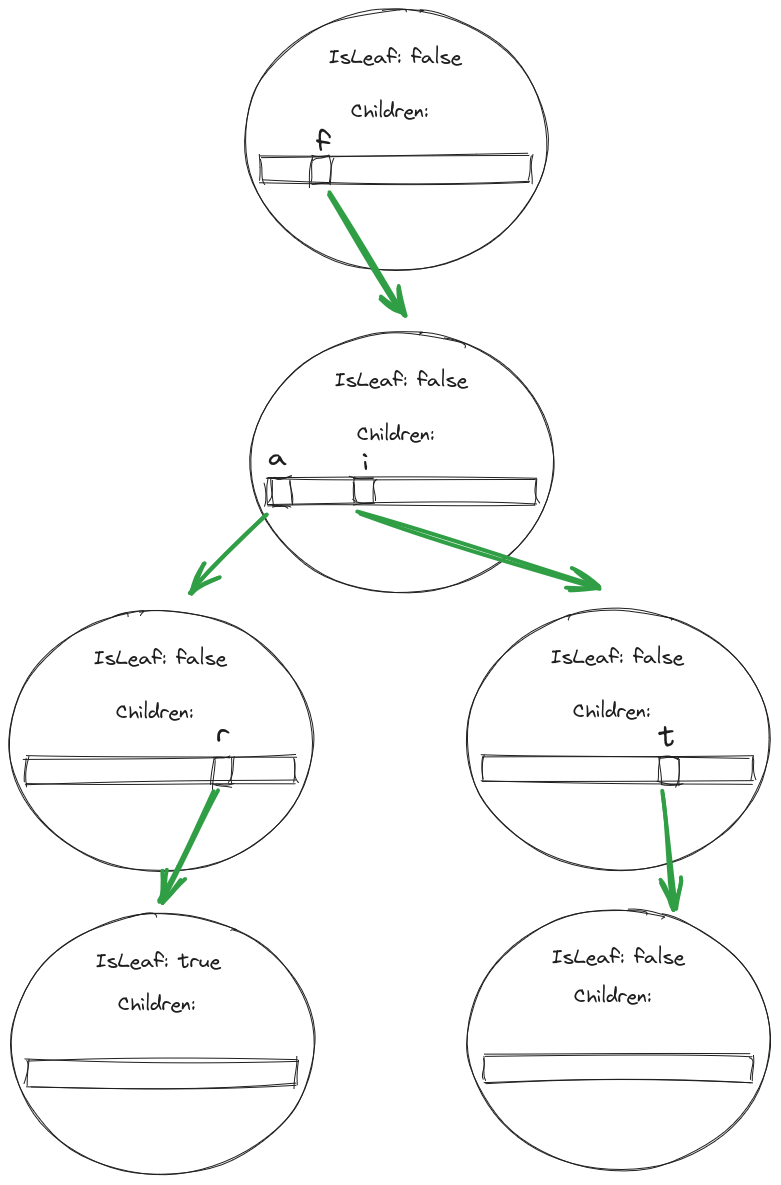

Trie Node Itself

The basis of a Trie tree is the Trie node itself. That looks something like this:

Or in pseudocode:

struct TrieNode

Children TrieNode[Alphabet-Size]

IsLeaf boolean

end

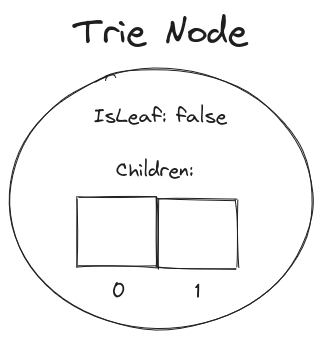

Recall that a Trie node has no value; the value is defined by the node’s index in the parent node. How do we determine this index? Recall, a Trie node has m child nodes for each node, with m being the size of the alphabet. What does that mean?

Let’s use an example. If our alphabet is binary, consisting of ‘1’ and ‘0’, with an alphabet size of 2, that means the node will have an array of size 2.

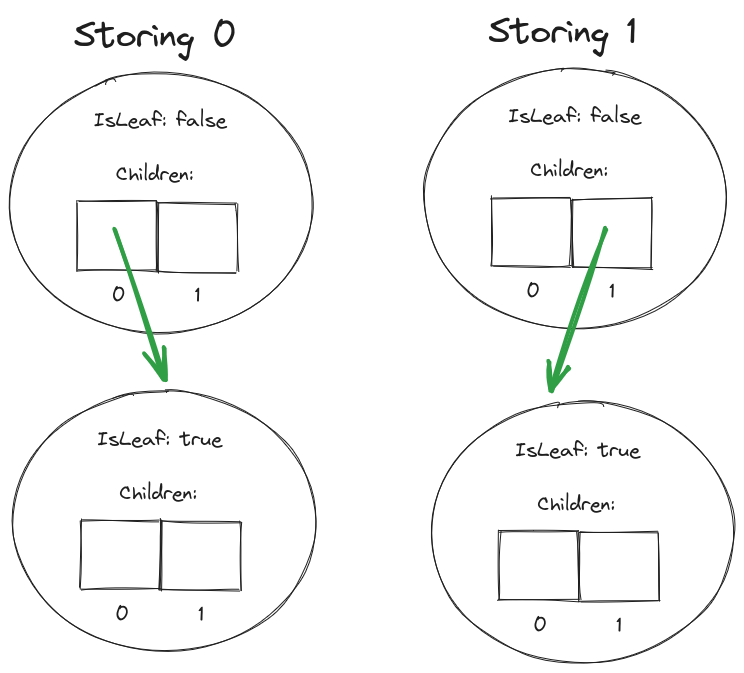

We can use the index where the child node is stored to record the value of the child node. If we want the node to have the child ‘1’, we point to that node from Children[1]. If we want the node to have the child ‘0’, we point to that node from Children[0].

The final step is just to mark the child node as a leaf, so that we know that it isn’t an intermediary node but is the end of a word. This is so if we decide to store ‘11’, we will know that ‘1’ isn’t stored when we reach that node.

Before reading on, if you are learning about the subject, I suggest you implement your own version of the Node, then come back and look at my version for comparison.

Go Code: Trie Node

const ALPHABET_SIZE = 26

type TrieNode struct {

Children [ALPHABET_SIZE]*TrieNode

IsLeaf bool

}

As you can see, the node itself is quite simple. The only thing to keep in mind is the alphabet size. We chose 26 because I will only be using the lowercase English alphabet. This can vary.

Insertion Operation

At this point, I will once again urge you to try your hand at figuring out how to insert a node into a tree of Trie Nodes, then come back here if you have issues. We will be approaching the insertion in a recursive manner.

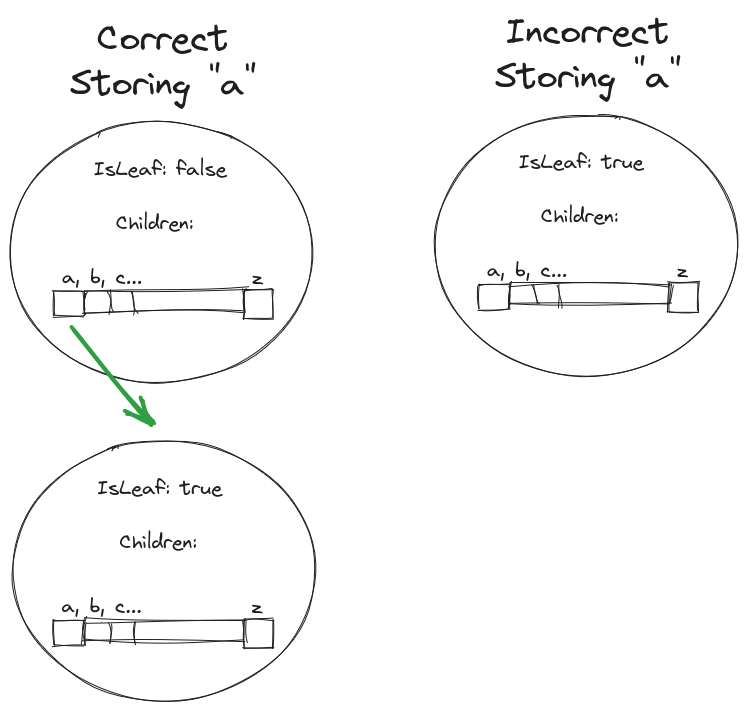

Base Case: the string to be inserted is empty

- Mark the current node as a leaf node

That is it. You might be wondering why the base case is an empty string. Remember, the Nodes have no values; their value is derived from their parents.

If we were to mark the node as a leaf when the string to store was a single character, how would we store that character itself? There always needs to be a child to store a value.

Default Case:

- Remove the first letter of the key

- Check if you have a child node that already exists with the index of that letter

- If it does not exist, create it

- Repeat the insert function on the child node with the rest of the key (omitting the first letter)

You might be wondering how we know what the index of a letter is. If our alphabet consists of continuous characters, we can simply convert them to an integer and modulus them by the size of the alphabet (‘a’ % 26, etc.). This will ensure that each letter goes to the appropriate index. If the alphabet is not continuous, then we will need to make it continuous and repeat the same thing.

Go Code: Insertion

Once again, try to code this yourself before you turn here. This is how I did it.

func (n *TrieNode) Insert(key string) {

if key == "" {

n.IsLeaf = true

return

}

letter := key[0]

if n.Children[letter%ALPHABET_SIZE] == nil {

n.Children[letter%ALPHABET_SIZE] = &TrieNode{}

}

n.Children[letter%ALPHABET_SIZE].Insert(key[1:])

}

Search Operation

Searching is even easier than inserting. This is what a Trie Tree storing the words “she,” “shells,” and “sea” might look like.

Given the above tree, try to think how you would search for a string. To search, we will have a similar base case to insertion:

Base case: empty string

- Return whether the node is a leaf or not

Default Case:

- Remove the first letter of the key

- Check that a child node with that letter exists.

- If it does not exist, then the tree does not contain the string

- Repeat the search function on the child node with the rest of the key (omitting the first letter)

Go Code: Search

func (n *TrieNode) Search(key string) bool {

if key == "" {

return n.IsLeaf

}

letter := key[0]

if n.Children[letter%ALPHABET_SIZE] == nil {

return false

} else {

return n.Children[letter%ALPHABET_SIZE].Search(key[1:])

}

}

Deletion Operation

At this point, we can already fulfill most of the use cases of the a Trie. Typically, a Trie is used for the search operation. For the sake of completeness, I will discuss deleting nodes.

First, let’s go over the approach to deleting a node; once again, our approach will be recursive.

Base Case - we are at the leaf node

- Mark the node as no longer a leaf

- If the node does not have children, delete the node itself.

Default Case:

- Remove the first letter of the key

- Check that a child node with that letter exists.

- Repeat the delete function on the child node with the rest of the key (omitting the first letter)

- Check if the current node has any children or is a leaf

- If not, then delete the node itself

This function is a bit more tricky, but I suggest you try your hand at your own implementation before you look at mine. In case you need a hint, think about what you are doing with the return value of the delete operation. You can make use of it recursively in a nice way.

Go Code: Deletion

func (n *TrieNode) Delete(key string) *TrieNode {

if key == "" {

if n.IsLeaf {

n.IsLeaf = false

}

if n.noChildren() {

return nil

}

return n

}

if n.Children[key[0]%ALPHABET_SIZE] != nil {

n.Children[key[0]%ALPHABET_SIZE] = n.Children[key[0]%ALPHABET_SIZE].Delete(key[1:])

}

if n.noChildren() && !n.IsLeaf {

return nil

}

return n

}

// This is a nice convenience function

func (n *TrieNode) noChildren() bool {

for _, v := range n.Children {

if v != nil {

return false

}

}

return true

}

Keep in mind that the check for the presence of children is completely optional. Setting the IsLeaf of a node to false is enough to remove it from the tree. The additional work we do is simply to reduce the amount of space the tree takes up and slightly reduce the cost of searches.

Take this diagram. This tree used to store both “far” and “fit.” We deleted “fit” by changing the final node in its search path to no longer be a leaf. If we search the tree, we will see that “fit” is no longer a member. However, we do have 2 nodes present that have no value. If we were to search for “fitness,” we would have to traverse 2 extra nodes before reporting that it is not present in the tree. It also means we have an additional 2 nodes in memory. There a drawbacks to both approaches.

Conclusion

I hope that this post taught you a bit about the Trie data structure. A Trie is an easy to implement tree that provides $O(1)$ checks for the presence of a string in a set. The competing data structure in this area is the hash table. In some situations, the Trie tree can be faster if there is a high chance of collisions in the table. For example, with many short strings.

The biggest drawback of the Trie is the amount of memory that it needs. The big brother of the Trie tree, the Radix tree, aims to solve this. Instead of storing each individual letter in a node, it stores combinations of letters, reducing the number of nodes needed. But that is the subject of a different post.

Full Go Implementation Code

const ALPHABET_SIZE = 26

type TrieNode struct {

Children [ALPHABET_SIZE]*TrieNode

IsEnd bool

letter byte

}

func (n *TrieNode) Insert(key string) {

if key == "" {

n.IsEnd = true

return

}

letter := key[0]

if n.Children[letter%ALPHABET_SIZE] == nil {

n.Children[letter%ALPHABET_SIZE] = &TrieNode{letter: letter}

}

n.Children[letter%ALPHABET_SIZE].Insert(key[1:])

}

func (n *TrieNode) Contains(key string) bool {

if key == "" {

return n.IsEnd

}

letter := key[0]

if n.Children[letter%ALPHABET_SIZE] == nil {

return false

} else {

return n.Children[letter%ALPHABET_SIZE].Contains(key[1:])

}

}

func (n *TrieNode) Delete(key string) *TrieNode {

if key == "" {

if n.IsEnd {

n.IsEnd = false

}

if n.noChildren() {

return nil

}

return n

}

if n.Children[key[0]%ALPHABET_SIZE] != nil {

n.Children[key[0]%ALPHABET_SIZE] = n.Children[key[0]%ALPHABET_SIZE].Delete(key[1:])

}

if n.noChildren() && !n.IsEnd {

return nil

}

return n

}

func (n *TrieNode) noChildren() bool {

for _, v := range n.Children {

if v != nil {

return false

}

}

return true

}